https://www.infirmiere-canadienne.com/blogs/ic-contenu/2025/11/03/depression-post-partum-parti-1-de-2

Part 1 of 2: overview of the integrated care pathway with two case examples

istockphoto.com/FatCamera

istockphoto.com/FatCamera

As an individual nurse, finding a way for patients without a primary care provider to access mental health services is a daunting task.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a two-part series. Part 2 will be published on November 10, 2025.

As Canadian nurses in a complex, inadequately resourced health-care system, we encounter moments every day when advocating as individuals feels insufficient (Heck et al., 2022). These moments often happen when patients are unjustly impacted by larger health system problems, such as when mental health patients cannot access services due to wait times or cost (Moroz et al., 2020). System problems must be addressed at the population level, with government and health-care leadership creating essential changes (Canadian Public Health Association, 2022).

Still, as professionals skilled in advocacy (Canadian Nurses Association, 2024), nurses work with others to find creative solutions. Integrated care is holistic, seamless care (i.e., improved access and continuity of care) achieved using collaboration and coordinated efforts from different health-care providers, disciplines, organizations, systems and sectors (Goodwin et al., 2021). Addressing an advocacy need found during clinical practice, collaboration among Archipel Ontario Health Team members, Hôpital Montfort, and Ottawa Public Health led to a new integrated care pathway to give birthing parents with symptoms of postpartum depression without a primary care provider access to mental health services. Implementing our pathway mimicked the nursing process: assess the gap, identify the problem, plan and implement, and always re-evaluate (Toney-Butler & Thayer, 2023).

In this article, we describe this integrated care pathway structured according to the nursing process and two case examples. We also review barriers encountered and overcome during implementation, and reflections worth sharing with others who might engage in similar projects. Although our experience is based in Ottawa, we believe these are insights that would be applicable to most jurisdictions across Canada.

Assess the gap: mental health services for birthing parents case study

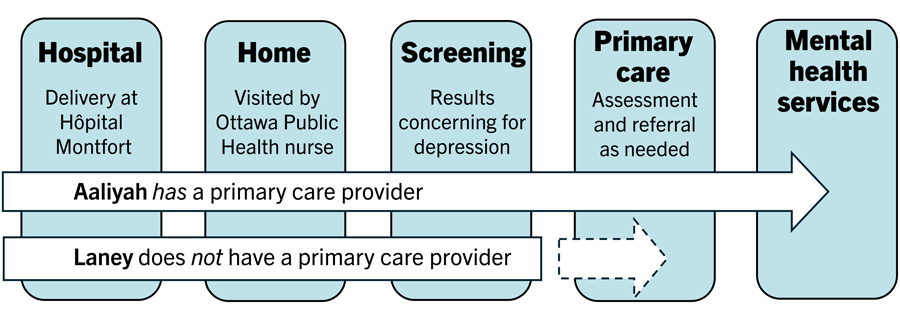

Two clients, who will be named Aaliyah and Laney, both give birth at Hôpital Montfort’s Family Birthing Centre. Before discharge, a public health nurse offers them access to Ottawa Public Health’s Healthy Babies, Healthy Children programming at home. Both parents accept the service. As recommended by the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) (2018), during their home visits the Ottawa Public Health nurse performs routine screening for postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (Levis et al., 2020). Postpartum depression is characterized by enduring and severe depressive symptoms with serious impacts on the health of parents and their families, including suicidal ideation and poor parent-child bonding (Mughal et al., 2022).

The screening results for Aaliyah and Laney are concerning for depression, meaning the nurse now has a responsibility to ensure appropriate follow-up (Waqas et al., 2022). Aaliyah has a primary care provider. The nurse sends her results to the provider, requesting a medical assessment and an as-needed referral to mental health services. With this support, Aaliyah receives care and eventually improves. Meanwhile, Laney does not have a primary care provider (also called an unattached patient). Because there is nowhere to send her results, Laney must self-present at an emergency department or walk-in clinic, where she experiences poor continuity of care and unpredictable circumstances such as long wait times (Bull et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Access to services is dependent on birthing parents having a primary care provider

Note. Birthing parents without a primary care provider experience a gap in accessing mental health services, revealing an opportunity to engage in advocacy and collaboration.

Note. Birthing parents without a primary care provider experience a gap in accessing mental health services, revealing an opportunity to engage in advocacy and collaboration.

Identify the problem: birthing parents without primary care providers

As an individual nurse, finding a way for patients without a primary care provider to access mental health services is a daunting task. In 2022, 2.3 million Ontario residents did not have a primary care provider, with this number predicted to reach 4.4 million by 2026 (Leiva, 2023). Lack of access to primary care is an unacceptable system problem requiring government and policy level changes. However, in the case of Aaliyah and Laney, a question presented itself: Could unattachedbirthing parents access mental health services through collaborative, integrated efforts?

The Archipel Postpartum Wellness Clinic team (from left to right): Sharlene Clarke, Ioana Negru, Natalie Rozon, Dr. Nadine Ostiguy, Camille Brunet, Louise Gilbert, and Josée Gauthier.

The Archipel Postpartum Wellness Clinic team (from left to right): Sharlene Clarke, Ioana Negru, Natalie Rozon, Dr. Nadine Ostiguy, Camille Brunet, Louise Gilbert, and Josée Gauthier.

Plan and intervene: the Postpartum Wellness Clinic

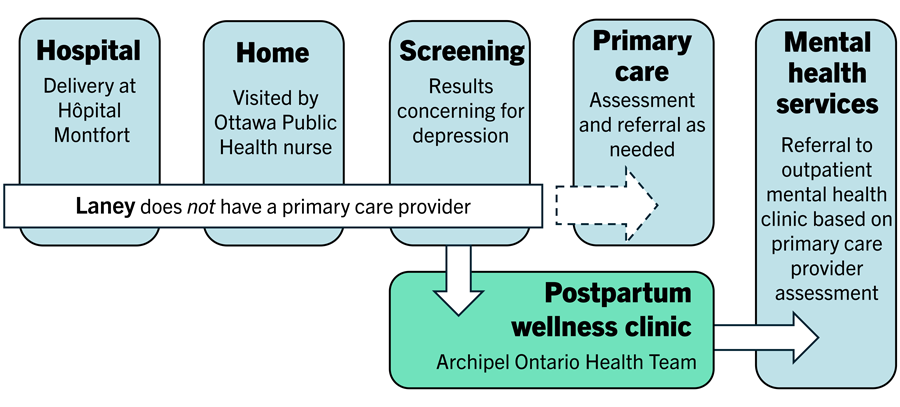

Focusing on a quintuple aim (see Nundy et al., 2022), RNAO has a program — Best Practice Spotlight Organization — fostering partnerships with organizations to implement their best practice guidelines. The Archipel Ontario Health Team Postpartum Wellness Clinic was established at Hôpital Montfort for parents like Laney (Figure 2, supported by RNAO’s Person and Family Centred Care guideline, 2015).

Based on postpartum depression screening results, Ottawa Public Health nurses referred parents to the clinic where providers facilitated access to mental health services as needed. In this way, collaboration became an advocacy tool, integrating the public health, community health, and tertiary care sectors. Sometimes organizational priorities only paralleled each other, but the overarching mutual priority was always the birthing parent.

Pooling resources also led to holistic care. For example, a problem left unresolved with public health resources alone could often be addressed through the hospital organization or community providers. Public health nurses integrated the social determinants of health. The provider had space to discuss parents’ other medical needs that weren’t directly related to depression. Team members also learned from each other — conversations were had about how to make parents feel heard and ways to collaborate in the future.

Figure 2 The Care Pathway for Unattached Birthing Parents with Postpartum Depression

Note. Collaboration among Hôpital Montfort, Ottawa Public Health, and members of the Archipel Ontario Health Team provided access to mental health services for unattached birthing parents (RNAO, 2023).

Note. Collaboration among Hôpital Montfort, Ottawa Public Health, and members of the Archipel Ontario Health Team provided access to mental health services for unattached birthing parents (RNAO, 2023).

Always re-evaluate: barriers, strategies and reflections

During implementation, our collaborative team evaluated ongoing barriers to pathway use and found strategies to overcome these barriers through regular, open discussions. Parents’ experiences of the pathway were also evaluated using optional interviews that informed further improvements. The greatest barriers are listed below, followed by strategies to overcome them and advice based on our team’s reflections:

Finding a centrally accessible, affordable, and sustainable physical space for the postpartum wellness clinic.

- Do not underestimate the challenge of finding a physical space for care.

- Collaborating with a large hospital meant more options. At Hôpital Montfort, space was finally made available.

- Being flexible about the space was important as options were limited. In this process, patients’ needs could not be compromised and were balanced with practical matters. For instance, a community space was preferable for our service, but the hospital was a more accessible location than other options.

Convincing primary care providers to participate and addressing concerns about increased workload.

- The providers who ultimately saw parents took a risk, as they did so without precise knowledge of program demand.

- Finding providers with value alignment and a strong belief in the pathway’s purpose created buy-in and motivated their participation.

Granting community providers practice privileges at the hospital (Montfort) required multiple levels of approval.

- Stakeholders already on the project with hospital knowledge and/or access helped the collaborative team understand and address the administrative process at Montfort.

- It is helpful to recognize team members as knowledge keepers and expert resources. Use your team to their full capacity.

- Based on our team’s experience, addressing practical and unplanned concerns may require more time, problem solving, and resources than anticipated.

Having strict inclusion criteria for parents using the pathway despite the different priorities and needs of the collaborating organizations.

- The Ottawa Public Health nurses working directly with parents identified ongoing problems/ways to improve, especially related to our inclusion criteria (e.g., nurses brought parents to our attention who could benefit from this service but did not meet criteria).

- Having open dialogue to make context-based decisions when possible was important (e.g., if parents did not meet our criteria exceptions were sometimes made after interdisciplinary and interorganizational conversations).

Ensuring key team members understood the pathway and knew their role in facilitating care.

- Our pathway leaders initially did regular presentations targeting nurses (the source of our referrals) and informal information sharing (e.g., during regular conversations, onboarding of new staff).

- In the future, we would also use online strategies (e.g., putting pathway information on involved organizations’ web pages or social media) to offer a detailed, easily accessible resource for team members and parents using the pathway.

Addressing miscommunications between parents and team members in the clinics (e.g., parents calling the wrong person about appointments, staff being unaware of the service and misdirecting parents at clinic visits).

- To keep parents’ trust, miscommunications were addressed quickly by the team and happened less as time went on. Initially, non-clinical leaders on our pathway team had to step in and coordinate care.

- Our collaborative team critically reflected on the miscommunications. Recognizing factors such as human resource issues (e.g., short staffing, high turnover, high workload) (Robinson, 2023) helped shift blame off individuals.

- The pathway was reiterated to staff through presentations and informal conversations. Frequent re-education was important and helped with this problem.

Realizing our design for communication during the pathway was too complicated and needing to streamline it.

- Regular interorganizational and interdisciplinary meetings with key professionals and organizational representatives were imperative to discovering and solving communication problems.

- Simplifying communication would have helped our pathway run smoother given the number of organizations and professionals involved.

- Because simplifying was not possible for our pathway, we would consider designating a care facilitator in the future to manage the heavy administrative demands.

Strength in collaboration

This pathway successfully bridged the gap in accessing mental health services for birthing parents without a primary care provider. We successfully overcame many barriers by being flexible, keeping parent needs central to decision-making, using our team members to their full capacity, and working toward strong communication. Client satisfaction surveys from parents who used the pathway were overwhelmingly positive. This integrative pathway reinforced creative problem solving among different providers, stakeholders and organizations who found unity from a shared belief that postpartum parents without a primary care physician deserved access to care.

As nurses continue to wait for necessary system-level changes to address injustices witnessed in their practice settings, participation in collaborative teams like ours offers space for advocacy.

Acknowledgements

RNAO’s Advanced Clinical Practice Fellowship supported this project. The creation and implementation of the Archipel Ontario Health Team integrated care pathway would not have been possible without the following team members: Sharlene Clarke (Archipel Ontario Health Team), Louise Gilbert (Ottawa Public Health), Geneviève Mosher (Ottawa Public Health), Manar El Malmi (Ottawa Public Health), Josée Gauthier (Ottawa Public Health), Nadine Ostiguy (primary care physician), Camille Brunet (Hôpital Montfort), Dania Versailles (Canadian Mental Health Association – Ottawa branch), and Stephanie Bonenfant (Montfort Renaissance).

References

Bull, C., Latimer, S., Crilly, J., & Gillespie, B. (2021). A systematic mixed studies review of patient experiences in the ED. Emergency Medicine Journal, 38(8), 643-649. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-210634

Canadian Nurses Association (2024). Advocacy Priorities. [Web page]. Canadian Nurses Association. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/policy-advocacy/advocacy-priorities

Canadian Public Health Association. (2022). Strengthening public health systems in Canada. https://www.cpha.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/advocacy/strengthen/strengthening-ph-systems-brief-e.pdf

Goodwin, N., Stein, V., & Amelung, V. (2021). What is integrated care? In V. Amelung, V. Stein, E. Suter, N. Goodwin, E. Nolte, & R. Balicer (Eds.), Handbook integrated care (1st ed., pp. 3-27). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69262-9_1

Heck, L., Carrara, B., Mendes, I., & Arena, C. (2022). Nursing and advocacy in health: An integrative review. Nursing Ethics, 29(4), 1014-1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697330211062981

Leiva, K. (2023, November 7). More than four million Ontarians will be without a family doctor by 2026. [Press release]. https://ontariofamilyphysicians.ca/news/more-than-four-million-ontarians-will-be-without-a-family-doctor-by-2026/

Levis, B., Negeri, Z., Sun, Y., Benedetti, A., Thombs, B., & DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) EPDS Group. (2020). Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 371, m4022. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4022

Moroz, N., Moroz, I., & D’Angelo, M. (2020). Mental health services in Canada: Barriers and cost-effective solutions to increase access. Healthcare Management Forum, 33(6), 282-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470420933911

Mughal, S., Azhar, Y., & Siddiqui, W. (2022). Postpartum depression. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/#:~:text=Postpartum%20depression%20most%20commonly%20occurs,women%20living%20in%20urban%20areas.

Nundy, S., Cooper, L., & Kedar, S. (2022). The quintuple aim for health care improvement: A new imperative to advance health equity. Journal of the American Medical Association, 327(6), 521-522. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.25181

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. (2015). Person- and family-centred care. https://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/person-and-family-centred-care

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. (2018). Assessment and interventions for perinatal depression (2nd ed.). https://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/assessment-and-interventions-perinatal-depression

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. (2023). Transitions in care and services. https://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/transitions-in-care

Robinson, R. (2023). Influence of staffing shortages on safety and communication in behavioral health (Publication No. 30313615)[Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Toney-Butler, T., & Thayer, J. (2023, April 10). Nursing process. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499937/

Waqas, A., Koukab, A., Meraj, H., Dua, T., Chowdhary, N., Fatima, B., & Rahman, A. (2022). Screening programs for common maternal mental health disorders among perinatal women: Report of the systematic review of evidence. BMC Psychiatry, 22(54). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03694-9

Andrea Bentz, RN, BScN, is a PhD candidate in the School of Nursing at the University of Ottawa.

Natalie Rozon, BScN, RN, is a supervisor in healthy growth and development at Ottawa Public Health.

Judith Makana, RN, BScN, MScN, CSIC(C), is a nursing professional practice advisor at Hôpital Montfort in Ottawa.

#practice

#care-models

#clinical-practice

#nurse-patient-relationship

#nursing-practice

#patient-education

#patient-experience